Two recent NMU alumni—Collin Richter ('17 BS) and Samantha DiGiulio ('16 BS)—received a National Geographic Society Early Careers Grant for a joint study on how last year’s hurricanes impacted reptiles and amphibians on St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Their June project was a follow-up to independent research they completed as NMU students at the same location during an advanced field marine biology course led by Professor Jill Leonard.

Richter said it important to monitor St. John because, unlike most islands, the bulk of it is protected area. Virgin Islands National Park comprises about 60 percent of its surface.

“There are 17 predicted species of reptiles and amphibians on the island: eight lizards, two snakes, one tortoise and six frogs,” he said. “The impacts of catastrophic storms are amplified on an island because it’s a smaller area with fewer species, generally, due to less immigration or emigration, and there are not as many outside influences. If you lose one species, what will take its place? How will that change other species’ specific niches and the function of the ecosystem?”

“When there’s a big disturbance, whether it’s from two major hurricanes in a season that level an island or from volcanic activity, it could easily wipe out an entire species or bring in a different one,” DiGiulio added. “Amphibians are great environmental indicators, so regular monitoring is ideal. If there’s strong evidence that something is wrong—for example, there are no frogs in a certain place anymore—you can determine why and advocate for change. With hurricanes becoming worse and more frequent and record temps being set earlier each year, examining the effects of changing climate and weather patterns on species’ populations and assemblages is especially important.”

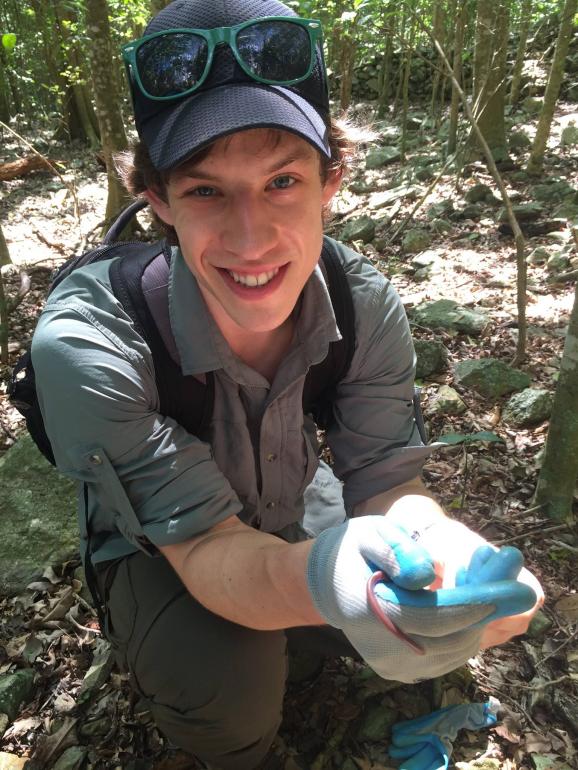

Richter and DiGiulio used visual encounter surveys, where they walked in a line, actively searching for different species along that line. They also did vocalization surveys, or listening for frogs calling. Other tasks included recording basic vegetation and measuring the visibility through a forested area to determine how much canopy cover has grown back after the hurricanes.

“On our previous survey, the delineation between habitat types was very clear,” he said. “This time around, the boundaries between forest habitats was unclear, due to loss of canopy cover and from large amounts of woody debris on the ground. We did not observe as high of an abundance of frogs, both on our visual encounter surveys and vocalization surveys. The three anole (small lizards) species seem to be doing well; all three species were seen across the island in multiple habitat types. We also observed ground lizards in high abundance, a species we had not seen on our previous trip. We’re excited to work up our data and hopefully see some patterns to provide clues as to why we observed some species and not others on this recent survey.”

The research partners will submit a report on their work to National Geographic and the National Park Service and plan to publish the results in a journal.

As NMU students, Richter and DiGiulio completed a joint independent study on St. John over spring break 2016 that used similar techniques as a 2003 U.S. Geological Survey of the island. They confirmed the presence of three species known to inhabit St. John that hadn’t been encountered as live specimens by the USGS. Because lizards are out during the day and frogs at night, the duo put in long hours to cover about as much ground in a week as the earlier survey did over two years, Richter said.

“The experiences under Jill’s guidance were extremely valuable,” added the former zoology major. “She leads research trips to Brazil and the Virgin Islands and I went on both each time they were offered. They solidified the kind of work I wanted to do moving forward. Freshmen may not think lab work applies to them yet, but they should start doing projects with faculty to learn the basic principles of research because it will help down the road in their jobs.”

It took DiGiulio, who majored in ecology, a couple of years to seriously immerse herself in lab and field research, but she said it paid dividends.

“Jill’s classes are for real. You’re not going to the Virgin Islands so you can sit on a beach; there’s an expectation that you’ll be productive doing research and that’s a good thing. Learning methodologies and data collection, entry and analysis are things I’ve continually used in different jobs since graduation. I haven’t really come across any other people who had opportunities like that as an undergrad.”