Northern Michigan University professor James McCommons recently published a definitive biography of George Shiras III (1859-1942), the groundbreaking wildlife photographer who honed his techniques in Michigan's Upper Peninsula. But that work often overshadows perhaps Shiras' most notable achievement: establishing the legal foundations for what became the Migratory Bird Treaty Act while serving in Congress. He was a seminal player in the early conservation movement, a longtime friend of Teddy Roosevelt and the namesake for a Yellowstone moose subspecies.

McCommons first became acquainted with his subject's pioneering photography years ago at a Munising bookstore. He leafed through a hefty two-volume set by Shiras titled Hunting Wild Life with Camera and Flashlight, which featured more than 950 photographs Shiras had taken over 65 years of traversing the woods and waters of North America.

Some of the images were captured with Shiras' crude flash technique at a camp near the settlement aptly named Deerton, about a half hour east of Marquette, Mich. It was inspired by an Ojibway “fire hunting” or “jacklighting” practice—now illegal—in which a cast-iron skillet full of flaming pine pitch was placed on the bow of a dugout canoe. While a Native American guide paddled a teenage Shiras and his brother along the perimeter of an inland lake, the boys were able to shoot deer rendered motionless by the trance-like effect of the approaching light.

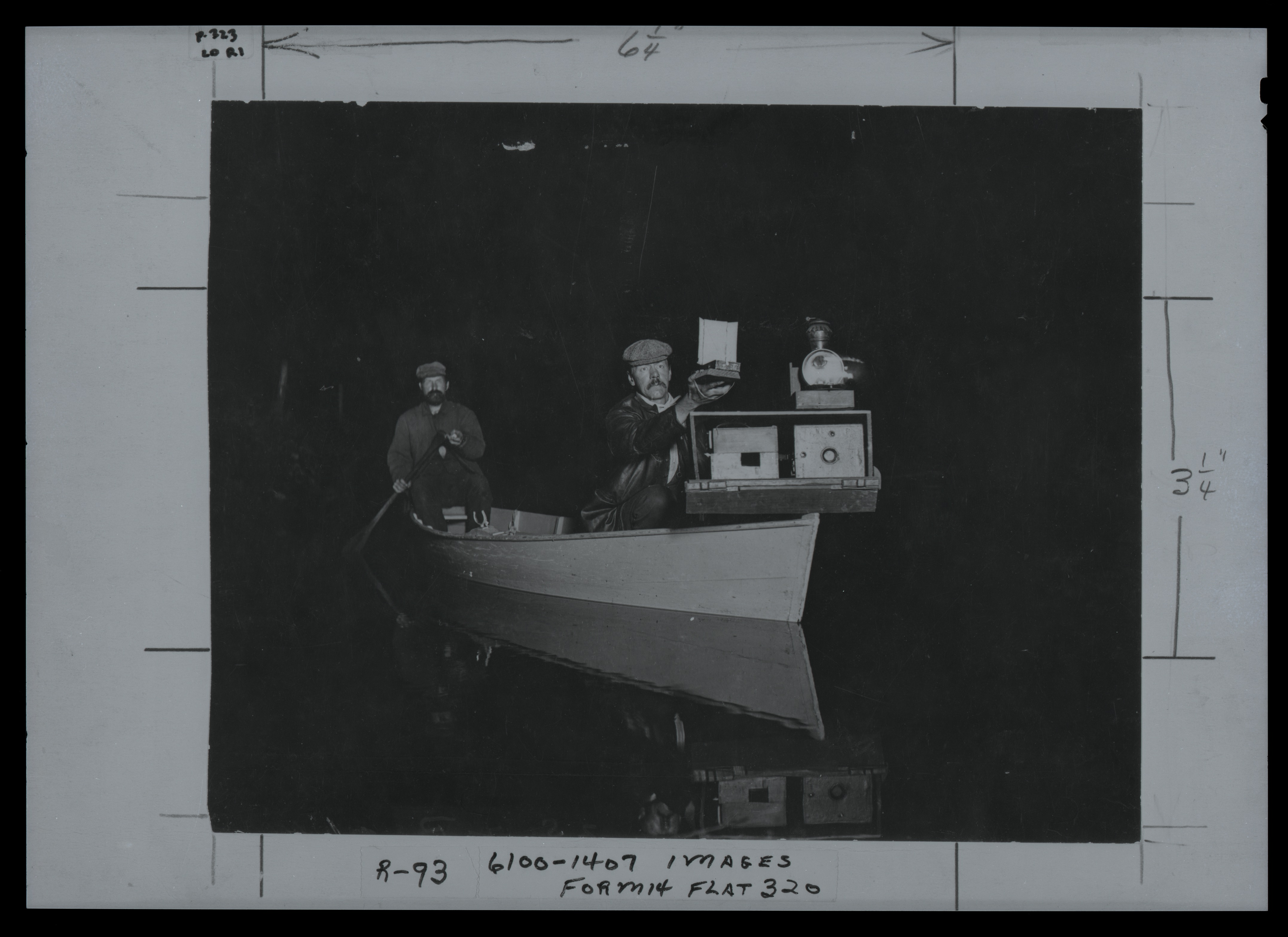

Around 1890, Shiras began applying the same principle to nighttime flash photography. He teamed up with John Hammer, a Norwegian machinist who had emigrated to Marquette. The duo fine-tuned the method for illuminating animals from a boat so they could capture images of them in their natural habitats. Shiras later developed a technique for taking pictures without being present. His “camera trap” invention was a primitive precursor to the modern trail cam.

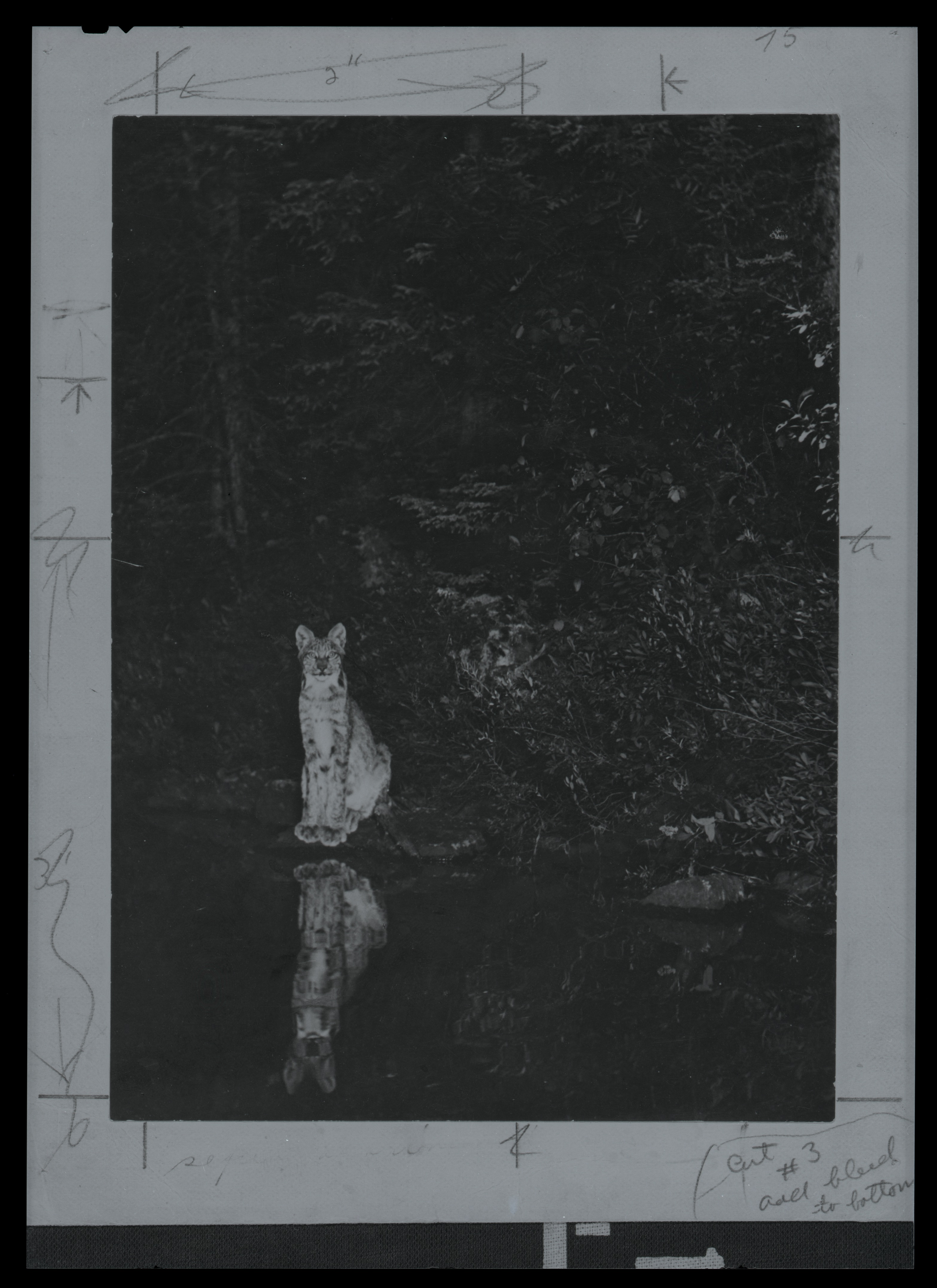

“It was a box camera holding a glass negative rigged to a chemical flare of magnesium and potassium chlorate powder,” wrote McCommons in Camera Hunter: George Shiras III and the Birth of Wildlife Photography. “When a deer stumbled into a trigger wire, the shutter released and the chemicals exploded with the force of a mortar, flooding the woods with a sizzling, brilliant light. … Pictures revealed wide-eyed, startled animals, muscles tensed for flight. It was a crude setup, but one that yielded extraordinary images.”

National Geographic, once largely a text publication, featured an article on Shiras' evolving photographic technique and showcased 70 of his images—deer leaping, a beaver gnawing on a tree trunk, raccoons scavenging and other animals engaged in nocturnal activities—in its July 1906 edition. Shiras served as a contributor to the magazine and later joined the board of the National Geographic Society, a position he held for 30 years.

In the same vicinity as the U.P. camp he had visited in his youth, on land formerly owned by his father-in-law Peter White, Shiras established his own camp. He returned there during summer breaks from his careers as an attorney in his native Pennsylvania and U.S. Representative in Washington, D.C.

McCommons wrote that the remote and tranquil refuge served as Shiras' “touchstone, the place where he formed his love for wildlife and expressed his passion for photography and wild country.” But it was also where he saw forests stripped down to stumps and wildlife and fish populations decimated to supply metropolitan markets. This sparked his resolve to promote conservation.

Shiras introduced legislation that, according to the Audobon Society, remains the primary tool for protecting non-endangered species—in this case, almost all native birds, along with their nests and eggs. He first raised the concept of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in Congress, worked for its passage as a lobbyist and put his expertise as an attorney to work establishing its legal foundation. He even helped the U.S. Attorney General write the Supreme Court briefs to defend the law in a 1920 landmark case challenging its constitutionality.

After his wife's death, Shiras returned to Marquette as a permanent resident. He died in 1942 and was buried in the city's Park Cemetery. In 2005, a moose took up temporary residence in the cemetery and had a propensity for emerging from the woods in the evening to feed on lily pads in a pond. McCommons was there one night and said he saw the moose saunter across Shiras' grave. “I couldn't help but think how appropriate that seemed, and how much he would have loved that.”

As McCommons discovered upon moving to the area to teach journalism classes at NMU, Shiras' legacy had been preserved through a number of Marquette locations named in his honor: a Lake Superior-fed swimming pool at Presque Isle; a shoreline park overlooking Picnic Rocks; a high school planetarium; a south side housing development; a municipal power plant; and a room in the public library that displays Shiras' nature book collection and deer photographs.

As a result of McCommons' research, an unfinished Shiras autobiography, letters and scrapbooks were gifted to the NMU and Central U.P. Archives by the University of Pittsburgh. NMU's DeVos Art Museum houses a number of his early images in its permanent collection and loaned some to a 2015-16 exhibition at the Museum of Hunting and Nature in Paris.

It is appropriate that McCommons received NMU's Peter White Scholar Award to support his work on the book. The award was funded with seed money from White's daughter, and Shiras' wife, Frances (“Fannie”).

McCommons said Shiras' most impactful contribution related to his innovative wildlife imagery may have come through encouraging sportsmen to appreciate animals and their natural environment through the lens of a camera. And now McCommons has made a significant contribution, using his writing skills to illuminate Shiras' important work as a photography pioneer and staunch wildlife conservation advocate in Camera Hunter: George Shiras III and the Birth of Wildlife Photography.

To see a slightly different and expanded version of this story, which appeared in Northern Magazine, the NMU alumni publication, click here.